Beyond “Art + Technology”

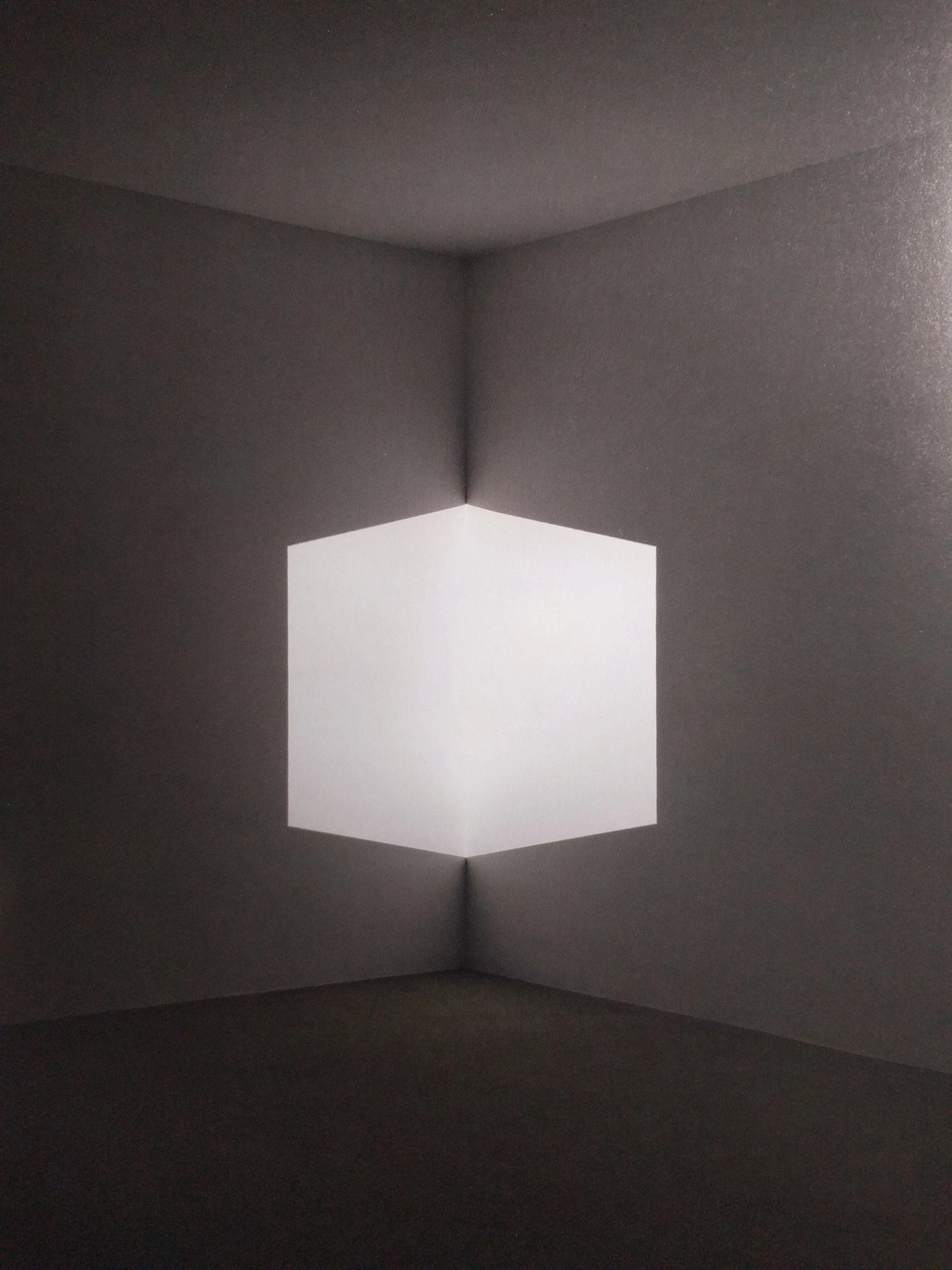

Afrum by James Turrell, courtesy of Andrew Schneider

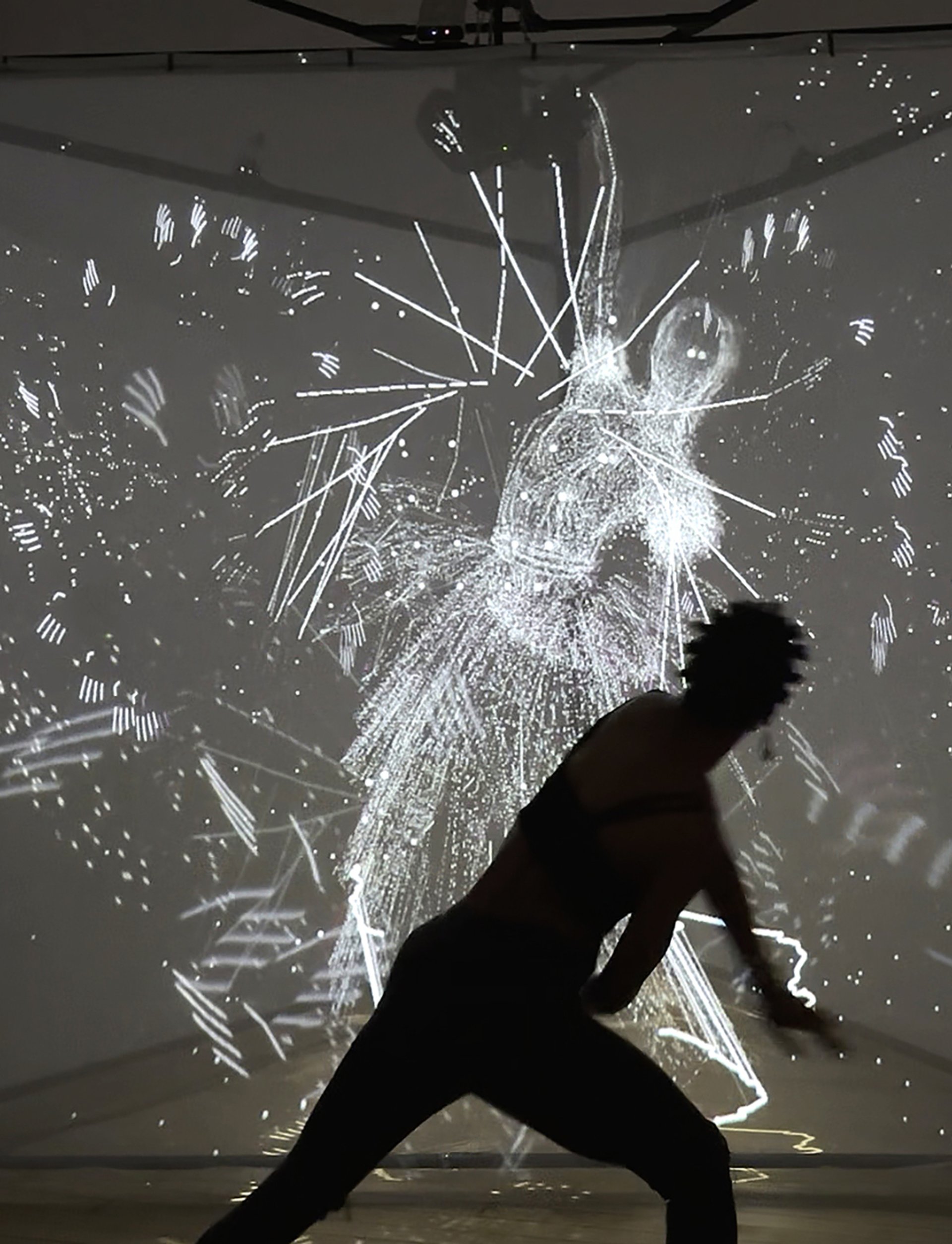

Hi. My name is Andrew Schneider. I make theater, installation, and dance. I often use science as a blueprint for staging. I study neurological, psychological, and physiological phenomena and try to get an audience to feel what it feels like to go through the experience of that phenomenon.

When I’m making a piece of theater that deals with hallucinations (for example), I don’t just want the characters to talk about hallucinations, I want to get you, the audience, to hallucinate. In order to get you to hallucinate, I have to alter your normal perceptions in a way that they probably very seldom get altered. I need to do something novel.

A way to do this perception altering is by using a highly sophisticated series of strobing lights, timed perfectly to the alpha waves happening in your brain (typically at 8-12hz). Scientists have come up with a projector mounted to a comfy chair that will beam this specific series of lights onto your closed eyelids in a lab with lots of equipment and cables and lab-looking stuff while you wear an EEG device that measures your brain activity. A novel experience for sure. And one reported to easily induce simple visual hallucinations in most people.

Another way to do this perception altering is just by turning off all the lights - like, all of them - like, all the way. Also a novel experience (how often in a world filled with LEDs embedded in everything do we get to be in a totally dark room - no difference between eyes open and eyes closed?). A primed, normally-sighted person can begin to experience simple visual hallucinations in as little as 5-10 minutes when their eyes remain open and their field of vision is presented with zero change in input. No input gives rise to neural noise. Neural noise gives rise to hallucinations.

Sometimes, when working with a dramaturgical stage effect like this, what is most practical is to use the projector setup. And sometimes what is most practical is to turn off all the lights. In either case, the goal is the same - to get the audience to feel or perceive something that they otherwise would not have been able to feel or perceive. To realize something about how their brain works.

The strange thing for me is, I get called an artist who works with technology if I use the former, and I don’t if I use the latter. Regardless, my interest is not in the tool, but in the outcome.

Same product, different grant application.

This points to a problem with how we talk about technology in the arts.

I want a future where “art + technology” doesn’t need the “+”. Counter-intuitively I think the way we get there is to continue funding artists who use technology. In the long term, the more fluent we get, the more the category dissolves. I want to get so good at it that you don’t see it.

When more artists have access, skills, and desire to use technology in their work (or when it simply isn’t a category to think about using or not using), we can get more fluent in our use - the field can begin to let go of novelty as a metric for success. Our use can become more integrated, more subtle, more nuanced.

In my own work I spend very little time thinking about whether something is categorized as technology - because to me, everything already is - the drum, the ballet slipper, the printed word, incandescent lighting, LED lighting, the MIDI controller, motion capture. Technology is a logistics layer, not an artistic category. It is a means of scaling, precision, and repeatability - not meaning. In fact, for me, the term “technology” could be substituted with “the only recently possible.”

The first show I ever made in college, I wanted the lights to turn on and off reminiscent of a rock show with the sound score I had created. Someone told me I could use the lighting console. It ended up being too complicated for me to figure out at the time. What I did instead was pick up 12 plug-strips from the hardware store and hire my roommate to switch them on and off in time with the music. I’ve since taught myself how to use lighting consoles, but the goal is unchanged. Input/processing/output can happen on a computer chip, or through a body.

I think that artists who don’t currently use technology can be reluctant to start because of what it possibly represents - the idea that a technologically driven practice is purposefully not forefronting the human experience. Grants set up for “artists using technology” can, on their surface, signal this. On the flip side, I think artists who get praised or are known for using tech can find themselves in a rut - keep doing what works. I find myself in this camp. If my next piece doesn’t use 3D audio, or performer tracking, or volumetric lighting, will funders be interested? My goal is to get an audience to question their own reality. I can do that with projectors and computers. I can do that with words and darkness. I can do that with bodies in space over time.

When I realized that we could induce hallucinations by turning off the lights - I also realized that’s what I had been doing all along. Paying very close attention to how you pay attention. In order to alter that attention. It’s not about me as an artist using technology anymore than a painter is an artist who uses brushes or a musician is an artist who works with musical instruments.

To me the future of art-making does not look more technological. It actually looks more human, less specialized, and more inclusive of what we mean when we say technology. Let’s keep thinking about “the only recently possible”.